Sodium Hypochlorite: An In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

Long before the days of laboratory precision, early chemists hunted for ways to lighten fabrics and disinfect wounds. In 1789, the French scientist Claude Louis Berthollet produced a solution in Paris by passing chlorine gas through sodium carbonate. This gave birth to what people called “Eau de Javel,” the direct ancestor of today’s sodium hypochlorite. For over two centuries, the substance saw new uses—cleaning up hospitals, making homes safer, and keeping cities sanitary. By the turn of the 20th century, mass production became possible, creating gallons of bleach every day for industrial and household use. During both World Wars, public health officials relied on it for water disinfection anywhere armies or civilians faced threats of infection. Plenty of folks today don’t know their white laundry shares a legacy with cholera outbreaks and battles against typhoid.

Product Overview

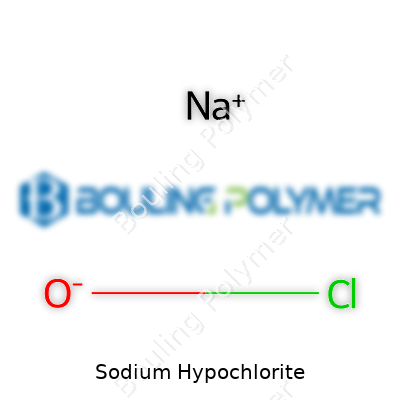

Modern sodium hypochlorite often arrives as a pale greenish-yellow liquid, with most bottles of household bleach containing 3% to 6% active chlorine. Industrial types clock in at close to 15%, sometimes even higher. Unlike many chemicals, sodium hypochlorite rarely sees buyers in powdered form, because it degrades and can be dangerously reactive if not carefully stored. Manufacturers, municipal water engineers, and everyday households reach for this product when cleanliness, disinfection, and safety matter most. Although bleach shows up in brand names like Clorox or Domestos, all these products share the same backbone—NaOCl—delivered in liquid forms suited for stripping stains out of white fabrics, killing algae in swimming pools, or even sanitizing vegetables in some food safety protocols.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Sodium hypochlorite solution usually carries a slightly pungent, “swimming pool” odor. It mixes easily with water, and it attacks dyes, bacteria, and even structural proteins. Chemistry textbooks list its melting point below zero and boiling point above one hundred and ten Celsius, so it remains stable over ordinary temperature ranges as long as light and heat don’t get out of hand. In my experience working with both household and industrial grades, exposure to sunlight quickly turns it into salt and water, robbing it of effectiveness. That's why vendors ship it in opaque drums. In terms of safety, its high reactivity with acids or ammonia means that improper mixing can turn any cleaning shift into an emergency room visit, driven by toxic chlorine gas.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labels for sodium hypochlorite leave nothing to guesswork. Every drum or bottle should clearly show the available chlorine percentage, pH value, batch number, and the recommended handling instructions. Depending on industry standards and national regulation, hazard pictograms warn users about skin burns, eye irritation, and environmental risks if dumped in large volumes. Any reputable supplier includes manufacturing and expiry dates, because decomposition reduces effectiveness and increases risk. Sometimes, technical data sheets also list trace impurities, especially if the product is meant for sensitive settings like water treatment or food processing.

Preparation Method

Commercial sodium hypochlorite production depends on passing chlorine gas into a cold, dilute sodium hydroxide solution. Chlorine reacts with the caustic soda, forming NaOCl plus sodium chloride and water. Factories must strictly control temperature and concentration to keep out unwanted chlorates, which show up if temperatures run too high or reaction times drag out. Most home chemistry sets can’t safely replicate this process. I’ve seen school demonstrations where tiny quantities work under a fume hood, but the real action happens in tank farms under active ventilation, with sensors watching to keep operators safe.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Mix sodium hypochlorite with acids, and the outcome becomes dangerously toxic—the mixture liberates chlorine gas. Combine it with hydrogen peroxide, and you get oxygen bubbles, but at a cost to the antibacterial effect. In cleaning, mixing bleach and ammonia creates chloramines, releasing deadly fumes. Even blending bleach with hot water hastens decomposition. Chemists and process engineers tweak formulation for special purposes, lowering or raising pH, or stabilizing with sodium hydroxide to lengthen shelf life. In textile bleaching, sodium hypochlorite sometimes gets replaced or buffered to curb fiber damage. Most wastewater treatment setups add it in pre-determined doses, ensuring just enough contact to sanitize without harming the environment. Each use case brings specific guidance, proving that sodium hypochlorite’s power comes as much from careful handling as raw chemical strength.

Synonyms & Product Names

Across the world, sodium hypochlorite finds names that reach beyond just “bleach”. International chemical references cite synonyms like “Javelle water,” “liquid bleach,” “antiformin,” or simply “NaOCl solution.” You’ll spot trade names on supermarket shelves or in industrial catalogues—Clorox, Milton, Dakin’s Solution (in wound care), and Poolchlor (in pool sanitation). Even without knowing a product’s brand, the unmistakable aroma often hints at its essential ingredient, so even folks without chemistry backgrounds recognize sodium hypochlorite by its scent alone.

Safety & Operational Standards

Anyone handling sodium hypochlorite must respect its danger to skin, eyes, and lungs. At home, eye-level droplets cause painful stinging or temporary blindness, while large splashes burn or corrode skin. Long experience shows that gloves, splash goggles, and good ventilation lower risk. Mixing in tight or unventilated spaces stacks up invisible threats—chlorine vapor or heat-driven decomposition fills air with irritants. Industrial settings deploy spill containment, automatic dosing, and staff training backed by government safety guidelines. OSHA in the United States and ECHA in Europe flag sodium hypochlorite as hazardous, requiring proper labeling and storage to cut down on accidental mixing or spills.

Application Area

Few chemicals see such wide usage as sodium hypochlorite. Water plants use it for municipal disinfection, making tap water safe year-round. Hospitals rely on high-concentration solutions for cleaning patient rooms, instruments, and even operating theaters, curbing the spread of infectious disease. In food processing, dilute hypochlorite keeps produce surfaces free from harmful bacteria, provided residues fall below regulated thresholds. Commercial laundries and households dress white cotton with confidence, trusting sodium hypochlorite to keep stains and odors away. Swimming pool maintenance teams keep algae and bacteria at bay with daily dosing, counting on rapid sanitization even during the busiest summer months. Agriculture and livestock operations adopt sodium hypochlorite for disinfecting equipment and animal housing. I’ve met farmers who trust bleach more than any other cleaner for biosecurity, knowing that skipping a wash can put an entire herd or crop at risk.

Research & Development

Scientific advances often orbit around safety, shelf life, and environmental impact. Chemists keep searching for stabilizers that hold available chlorine without speeding up decomposition or creating toxic byproducts. Some teams investigate encapsulation or controlled-release formulations, designed for public health applications where gradual dosing or precision targeting matter. University and public sector labs track environmental breakdown, hoping to limit harmful chlorate and chlorite formation. In medical contexts, researchers study ways to balance antimicrobial effectiveness with tissue compatibility, developing wound irrigation fluids or topical creams from modified hypochlorite solutions. Even formulation for use with new types of plastics, textiles, and membranes keeps R&D departments active, since incompatibility can mean ruined equipment or reduced product lifespan.

Toxicity Research

A century’s experience makes clear that sodium hypochlorite can inflame mucous membranes, blunt the senses, or trigger asthmatic attacks in sensitive people. Laboratory studies back this up—high doses damage aquatic ecosystems, stripping oxygen and harming fish. Accidental mixing with ammonia or acid cleaners causes more than five thousand American poison center calls each year, according to the American Association of Poison Control Centers. Chronic overexposure at work may create respiratory symptoms, though proper personal protection usually prevents lasting harm. Regulators and scientists review toxicological findings regularly to refine workplace exposure limits and home use instructions. With disinfectants under scrutiny post-pandemic, authorities remind users to dilute correctly and rinse surfaces to avoid chemical residue ingestion.

Future Prospects

Environmental pressures and shifting regulations push manufacturers to improve formulas and limit unnecessary chlorine release. Some startups focus on greener bleach variants, adjusting pH, stabilizer load, and packaging to ease end-of-life cleanup. Globally, emerging markets demand scalable sanitation tools, especially as disease outbreaks threaten under-resourced populations. In wealthier areas, new research peers into electrochemical generation—making sodium hypochlorite at the point of use, which slashes shipping and boosts freshness. Water safety, hospital hygiene, and disaster response will keep sodium hypochlorite firmly in the public eye. Still, progress pivots on education, technology, and respect for the risks and rewards packed into every bottle.

Keeping It Clean at Home and Work

People often reach for bleach to clean up stubborn messes or to tackle grime lurking in the kitchen or bathroom. That familiar smell—sharp, almost medicinal—signals the work of sodium hypochlorite. It's the backbone of household bleach and has proven itself across generations as a go-to solution against bacteria and viruses. Growing up, I watched my parents add a splash of bleach to mop water or laundry, especially During flu season. Its power lies in breaking down contamination on surfaces, stopping dangerous microbes from spreading.

Guarding Public Health

Walk into any hospital, and the scent of disinfectant hangs in the air. Infection prevention teams rely on sodium hypochlorite to kill bacteria, viruses, and fungi on medical instruments and floors. Health authorities like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) point to it as a trustworthy weapon against everything from norovirus outbreaks to hospital-acquired infections. In emergency situations, such as natural disasters or disease outbreaks, public health officials recommend sodium hypochlorite for disinfecting water and preventing diseases like cholera—a solution with broad reach, especially where resources run thin.

Ensuring Safe Water

Clean drinking water remains a critical need in many places. Water treatment plants use sodium hypochlorite in the fight against waterborne illnesses. It disrupts harmful microorganisms, allowing communities to trust the water flowing from their taps. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards require water systems to maintain safe levels of disinfectants, and sodium hypochlorite fits the bill. Having spent time volunteering in rural areas, I’ve seen firsthand how crucial this chemical becomes when other options simply don’t exist. A few drops in a bucket can transform unsafe water into something people can drink without worry.

Role in Industry and Agriculture

Beyond homes and hospitals, sodium hypochlorite finds work in industrial settings. Paper mills, for instance, use it to bleach wood pulp and remove stubborn dyes. Food processing facilities use it to sanitize equipment and keep products safe. Farmers depend on it to clean produce and irrigation systems, helping to cut down on crop disease. The scale of use in these sectors dwarfs what happens at home. The balance lies in keeping operations safe while respecting worker safety and environmental impact—something regulators and researchers keep a close eye on.

Risks and Responsible Use

There’s no question: sodium hypochlorite packs a punch. Misuse, though, causes trouble. Mixing it with ammonia or acids sends toxic gases into the air, threatening health. Improper dilution leaves behind chemical burns or damages surfaces. Overuse harms lakes and rivers when runoff escapes into the environment. It’s up to each user—homeowner, facility manager, city water worker—to read labels, stick to guidelines, and wear protective gear. Public agencies and manufacturers can help by sharing clear instructions and encouraging responsible habits.

Room for Improvements

Many of us take for granted the clean spaces and safe water that sodium hypochlorite supports. Pushing for safer, more sustainable options makes sense as we learn more about long-term effects on health and the planet. Research on alternative disinfectants—such as hydrogen peroxide or ozone—offers promise, though each comes with trade-offs. Until then, education on best practices and clear warnings on products make a difference. Everyone—consumer, business, and regulator—plays a part in using this powerful chemical wisely.

Sodium Hypochlorite: More Than Just a Common Cleaner

Sodium hypochlorite has become a household name on bottles of bleach and strong-smelling liquid disinfectants. Many folks recognize that chlorine-like scent when scrubbing bathroom tiles or wiping kitchen countertops. It works fast. It’s cheap. It’s easy to find. But questions about its safety keep showing up, especially since public health messages started encouraging routine disinfecting at home.

The Science and the Real-World Use

People use sodium hypochlorite to kill viruses, bacteria, mold, and other germs. That much is true, and there’s no shortage of research backing it up. Hospitals and clinics have relied on it for decades. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, plus countless infectious disease specialists, recognize it for dealing with dangerous pathogens, including norovirus and the virus behind COVID-19.

A solution of sodium hypochlorite at 0.1% can destroy coronavirus particles on hard surfaces within a minute. Most household bleach bottles contain around 5% sodium hypochlorite, so a little dilution gives you strong disinfecting power. This isn’t just theory—store-bought products, when handled right, wipe out illness-causing germs in kitchens, bathrooms, and clinics.

Where Things Get Risky

Nothing good in life comes without a catch, and sodium hypochlorite is no different. Spills, splashes, or even fumes from mixing with acids and ammonia can irritate eyes, nose, throat, and lungs. Anyone scrubbing counters knows the sting on skin after using bleach without gloves. Plenty of people have learned the hard way that you can’t just pour it on every surface. On some metals and fabrics, long-term exposure leads to corrosion and fading.

Children and pets face bigger risks, since even a bit on the skin or in the eyes burns and causes lasting damage. Containers left open or stored within reach can spell trouble fast. Drinking water with concentrated sodium hypochlorite can be poisonous. Emergency rooms have seen cases where folks mixed bleach with vinegar, releasing dangerous chlorine gas.

Practical Ways To Use Sodium Hypochlorite Safely

It helps to follow the science and manufacturer instructions without skipping any steps. Always wear gloves and keep good ventilation in the cleaning area. Never mix bleach with ammonia, vinegar, or other cleaners. Stick to labeled dilution instructions; those symbols and charts serve a purpose, and a little goes a long way. Rinsing surfaces afterward keeps trace chemicals out of food and hands.

Store sodium hypochlorite well beyond any child’s reach and always use the cap securely. Check the expiration date—old bleach breaks down and loses punch, but it still harms skin and eyes. Label spray bottles clearly, so nobody mistakes them for water or a gentler cleaner. If skin exposure or a splash happens, rinse right away with running water.

Weighing Risks and Rewards

Sodium hypochlorite stands as a potent disinfectant, trusted for disease control and household hygiene for a reason. The important thing lies in respecting its potential to cause harm when overlooked, misused, or mixed with the wrong substances. Getting the facts from reliable sources like the CDC, checking product labels, and taking safety steps offers solid protection for households and workplaces.

Clean spaces matter, but so does the health of the people who take care of them. With a little knowledge and the right steps, sodium hypochlorite remains a valuable cleaning ally, not a dangerous risk.

A Chemical That Demands Respect

Many of us know sodium hypochlorite as the main ingredient in household bleach. Its main job is to kill germs and disinfect, but in large amounts, like those used in water treatment or industry, it takes on a whole different level of risk. This chemical breaks down quickly if you handle it like a household cleaner left under the sink. Heat, sunlight, and certain metals can turn it into a major hazard; all it takes is a little negligence or improvisation.

The Real Reasons Storage Matters

Anyone who’s handled sodium hypochlorite in bulk knows it does not play nicely with others. Even stainless steel tanks can corrode and release unwanted byproducts over time. If you use the wrong materials, you risk leaks and dangerous chemical reactions.

This isn’t some paperwork formality, either. The CDC and EPA regularly warn professionals about the consequences of storing sodium hypochlorite in containers made with iron, copper, or nickel. It doesn’t just weaken the container walls—these elements actually speed up the breakdown of the chemical, leading to pressure build-ups and toxic gas releases. The infamous "bleach and ammonia" scare comes to mind, but even simple contact with sunlight or metal piping can trigger problems.

Essentials for Safe Storage

Plastic tanks made from high-density polyethylene (HDPE) or fiberglass-reinforced plastic last much longer. These materials resist chemical attack and don’t introduce stray metals into the solution. All fittings and valves should follow this same philosophy. Even the gasket material should stand up to sodium hypochlorite’s aggressive nature.

Every sodium hypochlorite tank should have a strong roof over it or live inside a shaded building. Heat and sunlight both speed up decomposition, which wastes product and could set off dangerous reactions. I’ve seen clear liquids grow cloudy and yellow, and heard cases where pressure in a tank became a real concern—all because a tank sat in the sun. Even if the operation saves a few dollars up front by skipping the shelter, the repair bills and cleanup costs quickly erase any savings.

Minimize Danger by Planning Ahead

Routine inspections matter with this chemical. Leaks can start slowly, making their way through pipe joints and fitting threads. Early detection through simple visual checks usually solves problems before they spiral. You don’t leave sodium hypochlorite sitting for months on end, either; old solutions break down and lose their strength. Shorter storage periods over more frequent restocking keep concentrations high and tanks safe.

Operators need easy access to emergency showers and eye wash stations nearby—this isn’t overkill. Accidents happen in the blink of an eye, and having the right response tools can prevent a bad day from becoming tragic. Sharing clear instructions with everyone on site also helps. Emergency contact numbers, spill kits, and training sessions help plenty more than any poster on the wall.

Forward-Thinking Solutions

Sodium hypochlorite works wonders for public health, but the way people store it tells the difference between a safe site and a chemical disaster. Choosing the right construction materials, planning for light and heat, keeping equipment in top shape, and training staff reduces risk. Every local regulation—from OSHA to state environment departments—reflects a lesson learned the hard way. Following their rules keeps workers and communities safe while preserving the chemical’s power to protect and clean.

Understanding Sodium Hypochlorite in Daily Life

People know sodium hypochlorite mostly as the main ingredient in household bleach. Hospitals and water treatment plants rely on it for disinfection, but the stuff isn’t as simple as it seems in a plastic jug. I grew up in a family that ran a cleaning business; bottles of bleach lined the workshop, and a permanent marker scrawled “Caution” was our homemade warning sign. We learned early that this chemical packs a punch and doesn’t mix well with shortcuts.

The Real Risks: Skin, Eyes, and Lungs

Direct contact with sodium hypochlorite irritates or burns skin and eyes. Once, during a deep-clean of a mildew-smothered bathroom, I rubbed my eye after failing to spot a splash on my glove. It burned like fire, sent me running for the sink, and taught me more about chemical safety than any classroom had. Even a whiff in a small room can turn into a choking fit—bleach’s fumes carry a strong punch.

Mixing Hazards: Don’t Play Chemist

The urge to boost cleaning power by mixing different products can be strong, but combining sodium hypochlorite with acids like vinegar or toilet bowl cleaner releases toxic chlorine gas. Not everyone understands the risk until it's too late. There’s a reason mixing warnings crowd household labels. Inhaling chlorine gas sends people to the emergency room every year.

Personal Protective Gear: Not Just for “Professionals”

I’ve handled bleach in kitchens, laundry rooms, and commercial settings. Protective gloves always came first. Cheap latex disintegrates, so go for nitrile or rubber. Safety goggles stop splashes from finding your eyes. Long sleeves and decent ventilation aren’t optional; they form the difference between staying healthy and landing in urgent care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) spells out these steps clearly for a reason.

Storage Matters: Keep It Cool and Sealed

On hot days, my dad moved bleach out of the garage. Warmth speeds up breakdown, turning a potent disinfectant into a weak liquid. Sunlight makes matters worse. Bleach eats through metal, so keep it in the original plastic container—tightly closed and far from kids and pets. If the label peels off, replace it with a clear warning. These habits spared us ruined clothes, damaged tools, and more than a few scary moments.

Spills and Disposal: No Room for “Good Enough”

Spill a bit, and the sharp smell takes over the room instantly. Absorb small spills with paper towels, then rinse the area well. For larger spills, ventilate, suit up, and use plenty of water. Never pour extra sodium hypochlorite down the drain at full strength. Municipal wastewater systems can get overloaded, sending harmful byproducts into rivers and lakes. Diluting with plenty of water before disposal follows EPA guidelines, helping prevent environmental damage.

Education and Labeling: Real Protection Comes From the Start

Knowledge beats luck every time. Training, clear labels, and practical reminders at work or home keep people from costly mistakes. Employers need to offer regular safety talks about chemicals. Parents and teachers can help children learn respect for cleaning products before curiosity leads to accidents. The more informed you are, the better your chances of staying safe and healthy around sodium hypochlorite.

Real Risks Lurk Under the Kitchen Sink

Many households keep a bottle of bleach around for laundry or deep cleaning tough stains. This bleach often comes in the form of sodium hypochlorite. People sometimes grab whatever cleaning agents they have to tackle stubborn messes, thinking more is better. My experience with household cleaning started after I moved out of a family home. I remember my mother’s warning echoing in my head: never mix bleach with anything but water. I didn’t quite get why until I heard stories from both tenants and hospital staff who ended up in trouble after trying to create homemade cleaning cocktails.

Sodium Hypochlorite and Ammonia: A Dangerous Mix

If you mix sodium hypochlorite with ammonia-based products, you risk creating chloramine gas. This gas acts as a severe irritant, causing coughing, chest pain, and watery eyes. The mixture has sent people to the emergency room with breathing trouble or chemical burns. Bleach and ammonia often hide in toilet bowl cleaners, glass sprays, or degreasers. Even a small quantity creates a toxic cloud in an average bathroom, especially without adequate airflow.

Bleach and Acids: Chlorine Gas Risks

Mixing sodium hypochlorite with vinegar, drain cleaners, or products containing hydrochloric acid creates chlorine gas. The smell stings your nose, only hinting at the danger. Even mild exposure can cause coughing or burning sensations in the throat and eyes. In higher concentrations, chlorine gas can damage lung tissue and force immediate evacuation—something no renter or homeowner wants. Cleaning mold, toilets, or grout carries this risk if you reach for both a bleach bottle and an acidic bathroom spray.

Surprising Sources of Trouble

Some people forget that many multi-surface sprays, dishwashing liquids, or even antibacterial soaps contain active ingredients that react with bleach. These reactions sometimes create less-known byproducts or produce heat, which damages surfaces and increases accident risk. I once ruined a favorite shirt simply by mixing bleach and a ‘color-safe’ laundry booster, which didn’t seem risky from the label.

Safe Use: Simple Rules Make the Difference

Sticking to a single cleaning agent for each task keeps you out of harm’s way. Before reaching under the sink for another bottle, read every label. Manufacturers list warnings for a reason, and hospital visits spike after holidays or big cleaning bursts. If strong cleaning power is needed, rinse the surface thoroughly between products. Open the windows, wear gloves, and never assume that combining leftovers makes a cheap “super cleaner.”

Better Alternatives Exist

Plenty of effective cleaning solutions exist that don’t require bleach at all. Microfiber cloths work for daily messes and don’t release fumes. Store-bought enzyme sprays actually break down stains and odors without harsh chemical interactions. For disinfection, plain old alcohol-based solutions or hydrogen peroxide do the job when used correctly and separately. The CDC and EPA both publish lists of effective products for different situations.

Listening to Science Saves Lives

Research shows thousands of accidental poisonings occur across the US each year from improper product mixing. No amount of “DIY” internet advice should override guidance from poison control or health experts. Sodium hypochlorite disinfects well, but mixing it with anything except cool water causes more problems than it solves. Double-checking, reading, and a little patience lead to safer cleaning—and nobody wants to recreate a high school chemistry mishap where they sleep or cook.